On Stanley Kubrick (and my father)

19th July 2008

Last week on More4 there was a fascinating documentary entitled, ‘True Stories: Stanley Kubrick’s Boxes’. For reasons I will shortly explain, this excited me so much that I actually cancelled on a friend in order to stay in and watch it. Bad form I know, but, hey, you know, sometimes, in life, one has to, you know, just punctuate everything with a comma.

Four reasons for utter absorption in aforementioned documentary

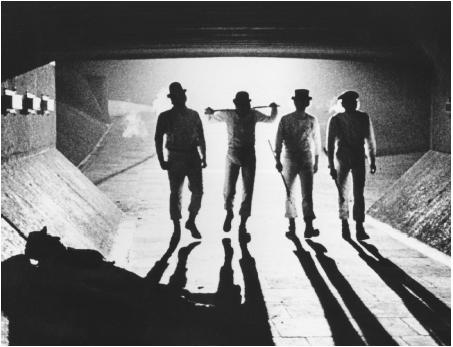

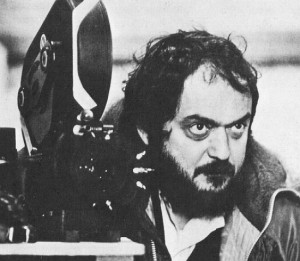

The documentary about Kubrick was the coming together of many things that I hold dear: Stanley Kubrick, for one, who needs no introduction from me.

Secondly it was written and fronted by Jon Ronson, certainly one of the most amusing columnists ever to grace the pages of The Guardian, and a very interesting film maker.

The third component of this holy quartet was Kubrick’s estate, Childwickbury. Childwickbury is one mile from the Hertfordshire town of Harpenden. I was brought up in Harpenden and every time I drove, or was driven, past the huge gates that guarded a path which seemed to wend as far as the eye could see, I would get a thrill. “I wonder what he’s up to with that big eye and big brain of his.” Rumour had it that he used to slip into Marks & Spencers in St Albans and buy sandwiches. Always using cash to avoid detection, no one knew what he looked like since he was so rarely seen in public and since, well, people just don’t look properly. “I’d recognise him!” I thought to myself. “I would! What could I ask him? ‘Stan, my man, gimme some skin! So, er, the prawn mayonnaise for you, then?’” During the filming of ‘Eyes Wide Shut’, Tom and Nicole were in the area and had dinner at The Blue Dog Café in Harpenden. I’d eaten there too! (nothing too extraordinary, but exciting enough when you’re young). Then one day I DID see him – at Ryman’s in St Albans. I bought post-its, paid up and walked out.

Go on Saul, describe how big the estate was

The estate the Kubricks lived on was enormous: imagine, if you will, an isosceles triangle: down one side is the Harpenden to St Albans road (5 miles). Back up the other side is the road from St Albans to Redbourn (5 miles). The shorter route from Redbourn back to Harpenden is the third side of the triangle (3 miles). Kubrick’s estate occupied a fair slice of that triangle such that the land stretched from one of the sides to the other, from mid-way down said triangle. That probably makes no sense, but the point is that as I drove past those gates on the way to St Albans, Mr K was probably still at least another mile away.

Stanley Kubrick did not play a major part in my childhood, but nonetheless it was fun – and bizarre – having him as a distant though distinguished neighbour. Imagine living on the same estate as Roman Polanski, or renting a room next door to David Lean. He was clearly the most exciting person to reside in the area (save for Nikki Davies, for personal reasons). Eric Morcambe also lived in Harpenden but that wasn’t really the same. Anyway I never liked Ernie Wise so Eric was tarnished by association. After I left home there was a rumour that Jimmy Greaves moved into the road opposite mine but, fine footballer and imbiber though he was, I doubt any of his goals were ever quite as good as The Shining.

That’s only three reasons, nobby

I used the word ‘quartet’ so there must be a further reason for my pleasure. And there was – the subject matter, and Kubrick’s boxes themselves. Ronson had written a feature for The Guardian back in 2004 describing his initial experience of searching through the Kubrick archives. I had found it so fascinating that I cut it out and a week later took it with me on holiday to LA where I handed it over to my cousin in the rundown motel we were staying at (and where, later that night he would be sick after an evening on the ales, then sick again in the bathroom of Circuit City the following morning as we searched for a new laptop for me, upon which I am currently hammering out this blog).

But I digress

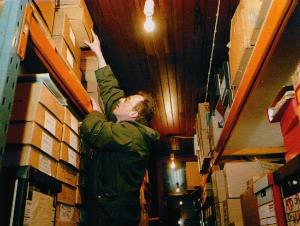

Jon Ronson received a call in 1996 from a man named Tony who said his employer wanted a copy of a documentary Ronson had made about the Holocaust. “Who is your employer?” asked Ronson. “I can’t tell you,” replied Tony. “Oh go on,” pleaded Ronson. “OK. It’s Stanley Kubrick.” Unfortunately Kubrick died in 1999, before Ronson got to meet him (as we shall see, things move fairly slowly in the world of Stanley Kubrick). However Tony called Ronson again in 2002 and invited him up to Childwickbury, to look through his employer’s vast archive. Ronson, no doubt slipping on his own saliva, took up the challenge.

The archives were housed in one thousand boxes, boxes that Kubrick had had specially designed by a firm in Milton Keynes after becoming dissatisfied with the original batch. The instructions by an anonymous hand (Kubrick) to G. Ryders of Milton Keynes read, “Lid to be not too tight, not too loose, JUST PERFECT”. An internal memo from the box makers had him listed as a “fussy customer”.

By their memos shall ye know them

Delightful and insightful detail abounded, not least the memo below:

“Dear Tony, Please make sure that we have plenty of melons in the house this summer. At no point must this number drop below three. Stanley.”

In 1992 Kubrick requested that his nephew take a picture of every single doorway in Islington (and latterly some of the South East) for the purpose of a brief scene in Eyes Wide Shut featuring Tom Cruise and a prostitute. The nephew spent a whole year doing this. “In the end,” deadpanned Ronson, “the scene was filmed on a set in Pinewood Studios.” More fascinating was the discovery of every fan letter K had ever received, all coded and neatly filed away. ‘P’ was for positive, ‘N’ for negative and ‘crank’ to indicate communication from a nutbag. The last of these was for police purposes: if Kubrick was gunned down by a lone nut (in the St Albans branch of Ryman’s perhaps, where he was a regular visitor), there would at least be a shortlist of loose cannons to consider.

Ronson tracked down one of the crank scrawlers. He turned out to be a formerly successful writer for television called Vincent Tilsley. Tilsley had written his letter after, marvelling at the way Kubrick was making films and changing cinema, he took the decision to deliver to ITV a six hour epic entitled ‘The Death of Adolf Hitler’ after having been originally commissioned for a play one third of that length. The night it appeared on television it was cut to shreds. Tilsley took a bottle of whiskey out into the rain, drank the lot, considered ending it all, then came back in and penned his rant to K. “If they’d done my play properly,” he said, “I’d be up in Kubrick’s league. So I’m going to get up there by talking to him from down here.” Tilsley spent the next two years writing and rewriting the first three pages of a project called The Birth of Jesus Christ, then quit to become a psychotherapist.

The Shadow of Obsession

It came to light that the Kubrick archives also contained two years’ worth of background information on a film about the Holocaust that, whilst Mr K was building up a huge body of research on the subject, Stephen Spielberg conceived, planned, auditioned for, shot, edited and released Schindler’s List. Is this madness? Where is the line that divides fastidiousness and obsession? As George Bernard Shaw once said, “Reasonable men adjust themselves to their environment. Unreasonable men attempt to change their environment to suit themselves. Therefore all progress is the work of unreasonable men.”

Was Kubrick’s obsessive attention to detail unhealthy or was it merely the behaviour of a man doing whatever he felt necessary to achieve his notion of perfection? Did he drive himself mad in the process? Was he already mad? I don’t know. And personally I couldn’t care less. How many reasonable men produce anything as good as Full Metal Jacket, Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear, Mrs Dalloway or Meat is Murder? I feel great compassion for those who suffer along the way, but if through their sufferance they leave behind something that provides unending pleasure for the rest of us, then they haven’t suffered in vain. Take away the melon memos or the filing of the fan mail and you lose the essence of the man, and with it all the wonderful films he made.

Not that anyone cares but

My opinion is that Kubrick’s obsessive attention to detail grew over those last few years – the last 19 of which produced only three films – because it could. This is the principle of diffusion, the definition of which is the spreading out of molecules to fill the space available. Shielded from the commercial pressures of being a young director trying to make his mark, free of any financial imperative, and protected by the Hertfordshire countryside, I believe he quietly and happily immersed himself in his quest: to seek and find artistic perfection. Perhaps such obsessive behaviour is not characteristic of a a normal man, but this, judging by the quality of his output, was not who he was. His children had grown up and he was surrounded by everything he needed. He was a completeist because he could afford, in every sense, to be one.

There must be a tipping point at which attention to detail becomes self-defeating, and certainly it seems Kubrick’s oeuvre began to tail off ever so slightly towards the end (though I still find Eyes Wide Shut to be a most excellent, atmospheric thriller and much underrated). Most great art is made when the artist is young, hungry (sometimes literally), out to prove something to the world and in a hurry. The best laid plans o’ mice and men are not always the best foundations for creative art. Still, Kubrick did what he did and, despite the rumours of his reclusive and unusual behaviour, by all accounts he loved every minute of it.

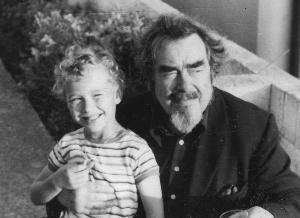

My Father

There is one more reason why I was so drawn to this programme. The notion of getting under the skin of someone now dead is, for me, an appealing, even a romantic one. My father died in 1998, the year before Kubrick, and whilst I knew him well during our time together, he was very much an older father and after his death it struck me how little I knew of his earlier years. Like Kubrick he was not a straightforward man, and those who are not straightforward demand explanation. In the last few years I have attempted to understand him, and also to trace his movements, mainly through the study of a highly acclaimed essay he wrote about his hermetic years in the wilderness of north Wales, but also through interviews I have conducted with his now elderly friends.

Though most people come to family history later in life, I have had to act fast: as the lady I most recently interviewed pointed out, “if you don’t do it now, we may all be dead. Then you’ll have no one to ask.” It was she who told me that the woman my father was living with, later diagnosed as a paranoid schizophrenic and sectioned, had written to the Pope to inform him that the witches were poisoning the bread in Penrhyn, how my father went for an interview at the Portmeirion Hotel dressed in Wellington Boots “because he didn’t have any shoes, you see,” and countless other gems (for an essay about my father, please click here).

The Essence of Man

My father left behind five or six jotters full of thoughts, aphorisms, hope and despair that span his wilderness years. One day I will find the time to break the hieroglyphical code that is his handwriting, or perhaps hand them over to a handwriting specialist who will transcribe them for me (well, for my half-brother and me). When I do, I too will have an archive to pour over through which I hope to further understand a complex man, and to find his essence.

Ronson said that he was always on the look out for something that contained the essence of Kubrick. He believed he found it when at the very end of his years of sifting he came across an acceptance speech that Kubrick had filmed for an award he did not collect in person, months before his death. Dressed in a blazer and looking like a sweet, kind, cautious old man, he says, his Bronx twang still very much in evidence, “Anyone who has ever been privileged to direct a film also knows that although it can be like trying to write War and Peace in a bumper car in an amusement park, when you finally get it right there are not many joys in life that can equal the feeling.”

The Kubrick archives are now stored at the Elephant and Castle College of Printing in London where students can come and marvel at them in an attempt to understand how the combination of a brilliant mind and an overwhelming attention to detail produced some of the greatest films of all time.

Ronson concludes the documentary thus:

“I think Kubrick knew he had the ability to make films of genius – and to do that, when most films are so bad, there has to be method, and the method for his was precision and detail. I think these boxes contain the rhythm of genius.”

* * * * *

Sorry this was so long – so if you’re still there, thanks for sticking with it. I hope it was rewarding.

TTFN,

Saul